The Texas Rangers and World War I

by Rusty Bloxom

Research Librarian

Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum

The World Goes to War

During the early years of the 20th Century, the nations of Europe were bound by a rigid system of interlocking treaties and alliances. Europe was a powder keg, and the competition for the Balkans heightened fears that a minor conflict could trigger a war.

On June 28, 1914, a Serbian terrorist assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. One month later Austria declared war on Serbia and tangled alliances began to unravel. By August 4th, all of the great powers of Europe were at war, with Germany and Austria on one side and the Allies (Russia, France, and Great Britain) on the other.

The United States was determined to stay neutral in this European war. While many Americans were sympathetic to the Allies’ cause, some communities supported Germany. Almost all Americans, however, agreed with President Woodrow Wilson that the United States should stay out of the conflict. In the minds of most Americans, this was a European conflict.

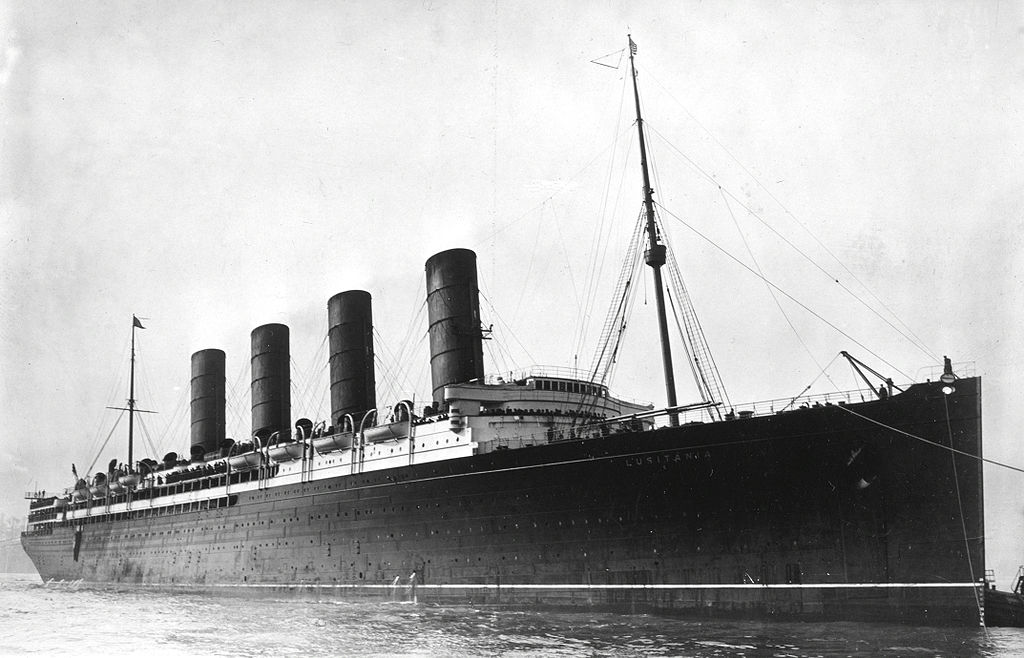

Neutrality proved extremely difficult. The British Navy blockaded Germany and mined the North Sea. The Germans retaliated by using their submarines (U-Boats) to blockade Britain and soon resorted to unannounced submerged torpedo attacks on ships bound for Allied nations. In May 1915 a U-Boat sank the British passenger liner Lusitania; of the nearly 2000 people who were killed, 128 were Americans. Outcry in the United States was strong, but President Wilson protested the attack through diplomatic channels and kept the US out of the war. Germany placed restrictions on the use of its submarines and the crisis passed.

Make the Kaiser Dance: America Enters World War I

By January 1917, with the war on land hopelessly stalemated and the hardships from the blockade becoming critical, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare. Knowing that this would likely bring the United States into the war, German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann sent a telegram to Mexico proposing that they declare war on the US with Germany’s support. Though the Mexican government rejected the proposal, British intelligence had intercepted it. In February, after five US ships had been sunk by U-Boats, the British gave a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram to the Americans. The revelation of Germany’s intrigue in Mexico seemed to confirm the suspicions of many that the Germans had been behind the violence there. This, paired with the outrage over the continued loss of Americans on the high seas, tipped the scales against diplomacy. On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany.

Patriotism soared as America quickly geared up for war. The Selective Service Act of 1917 went into effect in May and millions of young men reported for the draft. The Espionage Act of 1917 effectively criminalized opposition to the war. Hostility for Germany extended to anything remotely German – frankfurters became “hot dogs,” sauerkraut “liberty cabbage”, and dachshunds “liberty pups”. Many German-Americans also changed their names. Propaganda showing heroic Americans and demonic Germans abounded; Kaiser Wilhelm II was depicted as the inept yet evil “Kaiser Bill.” Civilian organizations like the American Protective League formed to keep a close eye on citizens for any sign of “disloyal” disenchantment with the war effort.

The military build-up progressed steadily as National Guard units and draftees were called up and organized. Most of the Regular Army was recalled from the Mexican border, but several cavalry and infantry units remained to guard the Rio Grande along with the Texas Rangers and other agencies.

American soldiers began arriving in France in June 1917. In the months to come, the American Expeditionary Force grew to over a million men. The US “doughboys” would prove to be a decisive factor in ending the war in November 1918.

Texas Rangers on the Border 1910-1920

“They are a grand set of men who are not afraid to do their duty”

- Mrs. R.A. Cunningham, Brownsville, Texas, 13 August 1918,

to Governor William Hobby

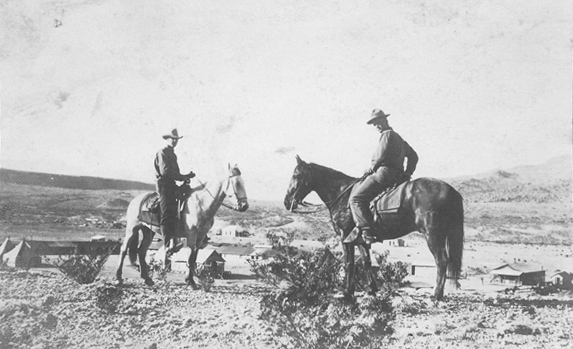

The Texas Rangers had been on the border with Mexico for almost a century at the time of World War I. From their inception in the 1820s, Rangers had fought bandits, rustlers, smugglers, and other outlaws who crossed the Rio Grande to ply their illicit trades. In 1910 Mexico erupted into revolution. Rebel bands in northern Mexico fought the Mexican Army and each other. Gunrunning from the United States and raids and rustling from Mexico increased all along the border. Revolutionaries retreating from Mexican Federal forces often fled across the Rio Grande. This Bandit War taxed the Texas Rangers’ small numbers, even after the U.S. Army joined them along the Rio Grande to counter the raids. German arms shipments to Mexico continued after the Revolution started; suspicions of deeper German involvement in Mexico grew after World War I began in August 1914.

In January 1915, authorities discovered a manifesto calling for an uprising among Tejanos in South Texas to reclaim the southwest for Mexico and eradicate the adult male Anglo population in the region. It came to be called the Plan de San Diego, after the Texas town in which it was assumed to have been written. Although it was far too ambitious to have worked, its discovery heightened the tensions along the border. The uprising never materialized, but raids from across the Rio Grande, aided by local insurgents, intensified as the raiders burned railroad bridges, attacked isolated ranches, and ambushed patrols. The Texas Ranger force added Company D under Captain Henry Ransom to combat unrest in South Texas. Ransom’s ruthless pursuit of this mission remains controversial.

The Texas Rangers often joined with US Army soldiers and Mounted Customs Inspectors in mixed patrols to scout the border and fight off the raiders. In March 1916 Pancho Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico, and the US Army sent a force into Mexico in pursuit. All along the line smaller military forces crossed the border, and in Texas they were often accompanied by Texas Rangers.

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, the Texas Rangers expanded to twelve companies. Although Rangers were called away to duties throughout the state, most were needed along the Border, where the pursuit of draft evaders trying to cross the Rio Grande joined the Rangers’ pre-war duties.

The end of World War I in November 1918 had little effect on the Rangers’ work on the border. The pace of operations slowed when the Mexican Revolution finally ended in 1920, but the banditry, cattle rustling, and smuggling did not stop. The Texas Rangers had been on the border for almost a century when World War I started. They are still on the border, facing many of the same challenges, a century later.

Going After Deserters in the Big Thicket

“It is like hunting a bob tailed squirrel with a nick in his left ear in the Brazos bottoms

in comparison to hunting these deserters.”

- Captain William M. Hanson

Walking Away from War

In the first decades of the 20th Century, the Big Thicket area of East Texas was still relatively remote. Most of the area was accessible only by poor roads through dense forest. Many residents paid little heed to people or events outside of the region, and distrusted of government. When the United States entered World War I and the draft was instituted, most of the young men of the Big Thicket answered the call and went into the armed forces, where their home-grown skills with firearms and field craft served them well. Some reported for induction, only to desert and go back to the East Texas forests later. Others simply disappeared into the woods when they received their draft notices.

Privates Sam Williams and Daniel Evans were drafted out of San Augustine County in 1917 and assigned to Company A, 360th Infantry Regiment at Camp Travis in San Antonio. While home on furlough in December, they decided not return to their regiment. Private Williams’ brother Henry had received his draft notice, but chose to ignore it. All three young men took to the woods to evade the authorities, while their families kept quiet and supplied them with food when they had to hide.

Death in Deep East Texas

In the summer of 1918, Adjutant General James A. Harley sent Texas Ranger Joseph Anders, Lee Saulsbury, John Dudley White, and Walter Ivory Rowe of Company D to assist San Augustine County Sheriff R.L. Watts in tracking down the deserters. On July 12th, White and Rowe went to the Williams’ farmhouse. They searched the house without finding the brothers, but instead of leaving they decided to wait on the front porch. About midnight White told the family to extinguish the last lantern. The Rangers remained on the porch, talking quietly in the dark, while the family waited inside.

At about 1:30 a.m. there was a burst of rifle fire from the front gate. An uncle who was staying with the Williams family later testified that he had rushed out and found John Dudley White lying mortally wounded and Walter Rowe bleeding heavily from a leg wound. Daniel Evans was standing in the yard holding a rifle; he said that he and Sam Williams had shot at the Rangers and that Williams ran away. Evans made a move to kill Rowe, but the uncle stopped him and went for help.

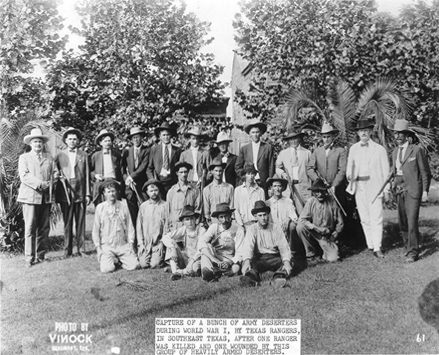

Anders arrived at the scene several hours later and wired Austin for reinforcements. Captain William M. Hanson and six Rangers joined with local and federal law enforcement and sixteen National Guard riflemen to track down the killers. The grueling search through the wilderness of San Augustine County was made more difficult as family and neighbors of the fugitives helped them evade the lawmen and soldiers, but by July 16th, the posse had located them. Hanson convinced the fugitives to surrender without bloodshed.

Sam Williams and Daniel Evans were court-martialed at Camp Travis for the murder of John Dudley White and the attempted murder of Walter Rowe. They were convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Once he had recovered from his wounds, Walter Rowe returned to duty with the Texas Rangers.

John Dudley White is buried in the Masonic Cemetery in Austin, Texas. His son, John Dudley White Jr., joined the Texas Rangers in 1942.

Loyalty Rangers: A Secret Service Department for the State

Nearly a year after the United States declared war on Germany, the national surge of patriotic fervor became state policy when the Texas State Legislature passed House Bill No. 15. Like similar Federal statutes, the Bill declared almost any form of opposition to the War to be an act of “disloyalty”. There was a strong implication that dissension was evidence of sympathy or even espionage for the Germans. “Disloyal” acts or utterances became state felonies that carried prison sentences of two to twenty-five years.

A new branch of the Texas Rangers called Loyalty Rangers was formed under Captain William M. Hanson to investigate violations of the Hobby Loyalty Act. Captain Hanson sent each of them a description of their duties, culminating with:

“You are… supposed to work under cover as much as possible, and in a secret capacity, and report all disloyal occurrences to this office….”

Unlike other Texas Rangers, whose authority was statewide, Loyalty Rangers stayed in their home counties to observe the behavior and activities of people in their communities. There were three Loyalty Rangers for each county in Texas – at a time when the regular Ranger Force was limited to 150 men, there were almost 800 Loyalty Rangers.

The Loyalty Rangers were drawn from all walks of life. Ranchers, farmers, and peace officers were recruited in large numbers, as were local merchants; others included bankers, lawyers, real estate agents, and barbers. Each went about their normal activities while keeping a watchful eye on their neighbors for any signs that their support of the American war effort was anything less than enthusiastic.

The rationalization for the Loyalty Rangers ended with the end of World War I, and though some tried to justify retaining their positions, all Loyalty Ranger commissions were withdrawn in February 1919, three months after the fighting stopped in Europe.