Texas Rangers - Life on A Scout

by Fred Wilkins

The following is condensed from Chapter 12 of The Law comes to Texas, by the late Frederick Wilkins, of Austin, Texas: State House Press, 1999. It is reprinted here with the permission of the author, Mr. Wilkins and State House Press. No other use of this material is authorized without the express written permission of the above named copyright holders. We wish to express our thanks to Mr. Wilkins and the late Mr. Munnerlyn for allowing us to use this material on our web page. Endnotes have not been included in this condensation.

Ranger Camp Life

When reading Ranger scout reports, reviewing the monthly returns, or examining laconic telegrams, it is easy to believe the Rangers were the stuff of legend and myth rather than very real men who possessed the foibles and faults of all men. Rangers had to eat and sleep, liked to have a drink and chased women on occasion, and a few were thrown out of the force for excessive fondness for some or all of these habits. Very little of the reality of daily Ranger life is revealed in official records; fortunately, most of the Rangers who wrote memoirs included descriptions of camp life which provide a portrait of the Ranger as a person rather than a manhunter.

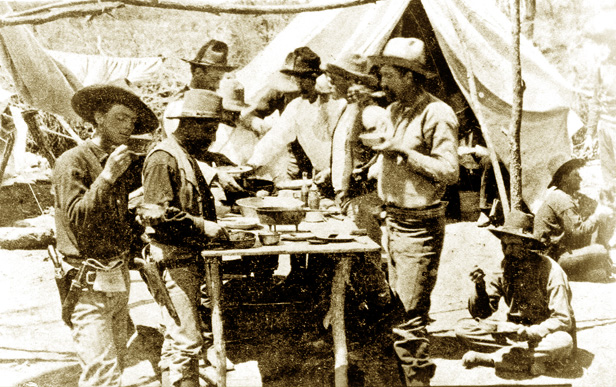

Food and shelter are the basic requirements for life; eating and sleeping for themselves and their mounts had a great influence on most Ranger operations. During the early years of the Frontier Battalion, the battalion's quartermaster supplied each Ranger company with a set ration consisting of flour, bacon, beef, coffee, sugar, salt, soda, soap, vinegar, pepper, candles, potatoes, onions and rice. A ration was the amount of each of these items an individual Ranger would consume in one day, and the company orderly sergeant was required each month to write out a list of how much was on hand of each item. There was some variation in the rations issued the companies because the quartermaster could not always find every authorized item in each company location.

Although the Rangers did not have a very varied diet, it was not bad for the time and probably better than most people on the frontier, who ate what they could grow or hunt. Many of the staple items were hard to find away from the settlements, and the Rangers often swapped surplus flour, rice and sugar for fresh milk and eggs and butter. Many accounts mention the ease of finding wild game and fish. At times the Rangers would camp near pecan groves or in an area where they could find wild honey. These natural supplements to their diet were always welcome and often vital on long scouts when supplies ran low.

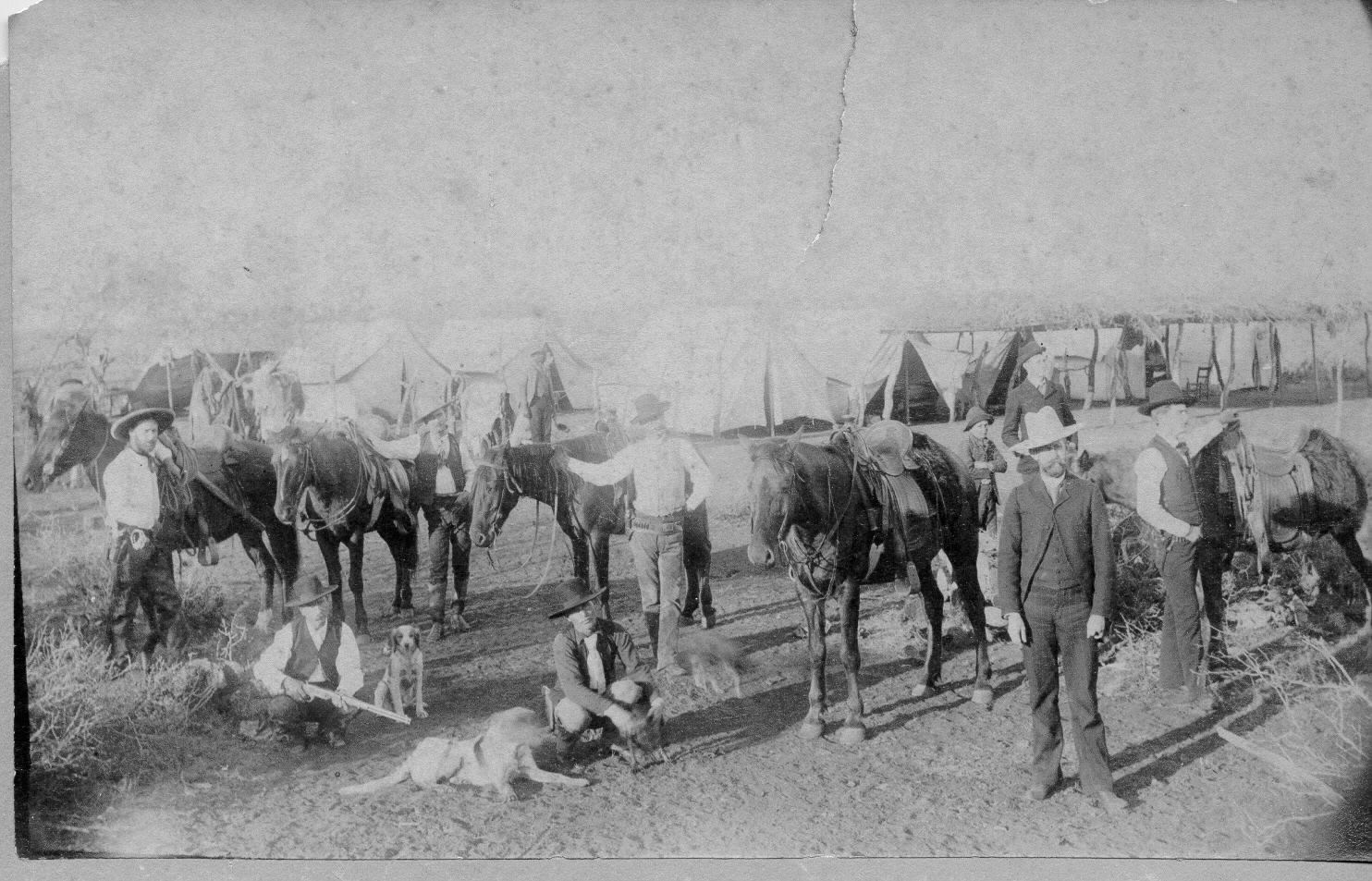

The canvas tents which the state furnished as the basic Ranger shelter worked well enough in warm months, but the bitter weather in North Texas required special winter quarters, generally log huts or cabins depending on how much timber was available. [James B.] Gillett describes how Company D constructed log cabins when they were in winter quarters near the San Saba River. Each mess of five men built a cabin about sixteen to each eighteen feet square with a fireplace and chimney. Rangers also took advantage of any building available: [George W.] Baylor's men were able to live in stone or abode houses while in Yselta, and [Charles L.] Nevill's company found some old buildings below Fort Davis which the men occupied in a combination of adobe and tents.

In earlier days a favorite pastime of the Rangers was horse racing, and many units developed race tracks. Generally betting was not allowed because the danger of hard feelings over losing money was too great;. . . The proscription of gambling also applied to card games; [George] Durham describes a card game in which he cheated in an attempt to beat an old hand who was a master poker player. The deception almost ended in a gunfight. Nevertheless, card playing remained a favorite way to kill time when off duty, and some companies even set the hours for play. When Company E petitioned for definite times, Lieutenant Gillespie published a company order to set the rules: men, when not on duty, could play cards between eight and eleven in the morning and one and five in the afternoon. If any man gambled for cartridges or after hours, he lost his privileges.

Mrs. Roberts [wife of Capt. Dan W. Roberts] wrote about a croquet set among the possessions of Company D while she was with the unit which the Rangers enjoyed. Music was also a favorite, although not every company was lucky enough to have musicians. Mrs. Roberts mentioned the number of Company D's men who played some instrument; Captain Roberts was a talented violinist, and the men formed their own band and played concerts for people when they were near a settlement or army post. Gillett mentions that the musicians of Company D were not the only ones; Company A also had a number of talented musicians. Major [John B.] Jones enjoyed the concerts by the members of his escort company.

When a company was near a town or army post, the Rangers took advantage of any social events taking place. Mrs. Roberts mentions one combined dance and quilting bee, lasting day and night, which people traveled considerable distances to attend. The Company D dandies always attended such festivities but sometimes on a take-your-turn basis when they had to pool their decent clothing so that at least a few might attend.

Most men signed on as Rangers with little more than the clothing on their backs. Although a Ranger was obligated to have a horse, saddle and arms in order to enlist, even these requirements were not always followed to the letter of the law. Especially in the early years, the state frequently allowed a promising recruit to enlist without personal weapons, furnishing his arms and deducting the money from his first pay. In late December 1874, Captain [Martin H.] Kenney, the battalion=s quartermaster, wrote Lieutenant [J. T.] Wilson in Company A and gave him a list of men who owed money for clothing or horses. Most of the sums are modest, suggesting the purchase of clothing, but a sixty-five dollar debit indicated reimbursement for a horse. Durham mentions arriving in Texas with only the clothing on his back and wearing the same outfit for over a year before he could save enough for a new outfit.

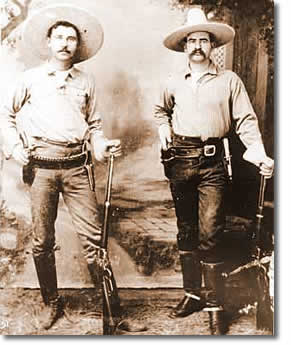

Photography was popular during this era, and there are many pictures of the Rangers of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The average Ranger of the late 1870s normally lived in his work clothes, which were also his dress clothes. He did not look like the movie cowboys; unlike the cowboy boots popular today, he wore boots almost knee high and cut square across the top with a high heel and somewhat pointed toes. Usually a Ranger's boots were the best item of clothing he owned. His spurs were heavy, with large rowels. A wide-brimmed hat was a necessity, and they were worn in almost every color and shape. The Ranger had long underwear, and his pants and shirt were generally of fairly heavy weight. he wore a vest, a handy place to keep a watch if he had one, coins, tobacco and any papers. In the colder portions of the state, or during winter, the Ranger wore a heavy coat manufactured of anything from thick cloth to buffalo hide.

Unlike the cowboys depicted on TV and in movie westerns, the Ranger carried his knife and pistol on a belt worn high on his waist; he needed his handgun ready at any time and could take no chances on a belt hung low on his hips. A number of contemporary photographs show Rangers wearing cross-draw holsters, a convenient way to draw a weapon when riding.

The grim, relentless manhunters were also practical jokers. Since Texas supplied the Rangers with little more than the opportunity to get shot, each recruit was eager to obtain anything free, and a favorite trick was telling new Rangers that the state furnished them with free socks. Naturally, the man issuing the free socks was the company commander, and the old hands would watch from cover as the new man approached the captain to ask for his socks. Captain Roberts of Company D always went along with the gag.

Some pranks were more physical in nature. During winter, when the Rangers lived in log cabins, a great favorite was blocking the chimney with rags. When the smoke forced the occupants to flee, other Rangers would rush up screaming Afire!@ then dash inside to throw outside all the possessions of the victims.

Jeff Milton, besides being a good man with a gun, was a champion jokester. One of his friends could never understand why his girl friend had dropped him and refused even to talk to him; he never knew Milton had confided to her in strictest confidence that her boyfriend was an escaped convict.

One day when alone in camp, Mrs. Roberts received some letters addressed to her husband, who was away on business. One letter was from Austin, and usually any message from the capitol was bad news; the Rangers asked her about the contents, certain it was news about cutting company strength. She finally told them they were right; the legislature was on another economy move and all men under five feet ten inches would be discharged. For some time the company was in turmoil as men measured each other trying to estimate heights to see if they had made the cutoff until Captain Roberts returned and told them it was all a joke. Mrs. Roberts said "the Rangers thought it was a good joke and did not hold it against me."

Not every Ranger spent his time in paying cards or thinking up practical jokes. When off duty, especially during the long winter evenings, some of them studied and eventually became lawyers, doctors, or other professionals. Probably about the same number of men, however, were unable to read or write, although some of these learned the rudiments during their enlistment. A number of the older men saved their money and purchased cattle and land; others not interested in being tied down to a ranch purchased a few head and had nearby farmers or ranchers keep their stock with the larger herds. . . A number of Rangers became large landholders when they left the service; Nevill, Gillett and [Pat] Dolan all had large ranches in the Trans Pecos, and [John B.] Armstrong became a major landholder in South Texas. Many Rangers went to work as ranch foremen or ranch managers. R. R. Russell saved his money, became a banker and one of the few Ranger millionaires. Perhaps the majority of Rangers, however, had a good time and spent their wages about as fast as they were paid.

The Rangers changed as Texas changed. Living conditions improved dramatically from 1874 to 1890, and to some degree the Rangers reflected these improvements. The men were still young and looking for adventure, but they were somewhat better educated and dressed better. In 1875 Gillett wrote about the necessity for gathering up all the good clothing in Company D to obtain a few complete and decent outfits for the local dances; a photograph of Company D in the mid-1880s shows every man in a coat and tie. The battalion picture of 1896 portrays each Ranger in a good "Sunday" suit, something almost unknown in the 1870s. Ranger [Alonso] Van Oden describes very matter of fact manner how he spent a month's pay for a new suit and a pair of boots, a commonplace expenditure by the 1890s.

Texas Ranger Mules

A few things remained constant during the quarter century, and one of the features of camp life has received little mention over the years. Much has been written about the celebrated Ranger horses, but each company also had a few mules for hauling the company wagon or for use as pack animals on long scouts. A tribute to the Ranger mules is overdue.

The mules, carefully selected and smaller than most of their breed, had impressive endurance and made possible the long scouts that became a Ranger trademark. They kept up with the horses and charged along with the unit in a fight. The Rangers swore the animals knew what was happening and enjoyed the battle. At least one was killed in action, and many others were cut free and lost.

Brave as they were, the feature that most impressed those who wrote about the mules was their sense of the ludicrous. They were animal comedians which, unless confined, wandered through the camps taking food from the Rangers. They delighted in frightening wagon trains by spooking other mules or horses hauling freight. Once, in Austin, a Ranger mule got loose and wandered about the streets until it ran into one of the new mule-drawn trolley cars; the Ranger mule charged the other mule which bolted and jerked the trolley from the tracks.

On scouts the little mules were laden with everything from Dutch ovens to ammunition boxes, frying pans, coffee pots, canned food, and forage, most of which made a terrific racket startling to other animals. The mules seemed to be aware of their ability to instill fear and would charge other animals to cause confusion. Orders finally had to be issued to keep the mules out of settlements and towns and away from road traffic. The mules' antics and abilities didn't change over the years; Gillett wrote about their antics in the 1870s, [Ira] Aten told the same wild tales in the 1880s, and even in the late 1890s Paine described [William J.] McDonalds mules and the wild charges.

So, after all their years of service, a belated tribute is hereby extended to the Ranger mules, essential features of camp and field who knew little of the law but understood duty.